The author is an associate researcher at the Raoul-Dandurand Chair, where his work focuses on the study and analysis of American politics.

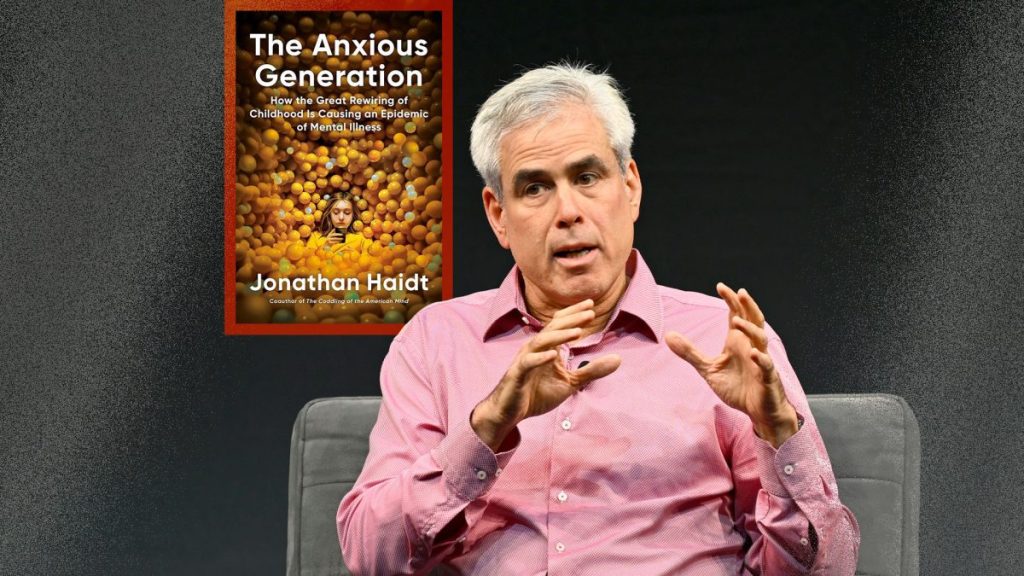

Jonathan Haidt is in a league of his own. Professor of social psychology and ethics, first at the University of Virginia, then today at New York University, he represents a rare creature: an intellectual whose ideas have real impact in public discourse . His TED talks have been viewed millions of times. His books are bestsellersand he is considered one of the great contemporary global thinkers.

Even rarer in this era of extreme polarization: his remarks often manage to bring together Democrats and Republicans, people on the left and people on the right. Perhaps because they are difficult to refute — and because they are particularly important.

This week, Haidt publishes his fourth book, which has already earned him an impressive media coverage. The Anxious Generation (the anxious generation) displays the devastation caused to an entire generation by smartphones and social networks.

Unprecedented mental health issues (measurable well before COVID–19 lockdowns), sharp decline in academic performance (for the first time in half a century, a generation of Americans is doing less well in school than the previous one) and difficulties in better establishing themselves in the adult world: the devastating psychological effects are clearly presented.

What is less often explained are the consequences of these psychological problems for American democracy.

Generation Z, which arrived on college campuses in the middle of the last decade, was the first to enter adulthood after being raised with social media. And, collectively, it displayed the triple psychological disorders of millennials — starting with anxiety.

Haidt mentions that before 2020, about 10% of young adults said they had suffered from depression; at the turn of the 2020s, it was around 30%.

The increase cannot simply be dismissed on the basis of less stigmatization of mental illness (the idea that younger people would see less of a taboo than their elders in admitting to suffering from a disorder), because this increase skyrocketing is not just observed in data from young people themselves.

From 2010 to 2020, hospitals recorded an almost 50% increase in the number of self-harm admissions among boys. Among girls, this was 200%.

Note that, although these increases are spectacular, the phenomenon continues to only affect a minority of young people.

But this minority is no longer marginal… and the rapid growth in mental health problems associated with the widespread use of social networks is worrying.

The university has always been a space for exploration, experimentation and openness. However, these members of Generation Z do not arrive in “discovery” mode… but in “defensive” mode, laments the author.

They were already anxious; the specter of having to confront ideas different from theirs, values strange to theirs, is no longer seen as a source of debate and exchange… but as a threat.

The modus operandi quickly became to limit the speech, to cancel the invitations made to certain speakers or to completely prevent them from speaking when they were on site – in addition to seeking to punish professionally, sometimes going as far as dismissal. , members of the community who made comments deemed too hurtful or threatening.

This phenomenon of “banishment culture”, originating from American university campuses, has for years been sometimes dramatized by some, sometimes minimized by others. One thing is certain, it is real. And, above all, he did not come alone.

Haidt highlights how, during the same period, the largest social networks have perverted public space beyond academia.

With “simple” additions like the option to “retweet” a message on the most sensational to gain notoriety and prestige in the virtual world.

This encouraged the extreme and most tribal voices to “build” legions of ideological disciples in the most homogeneous echo chambers possible, in perpetual conflict with members of the “other” tribe. In such an ecosystem, more temperate voices are quickly drowned out.

Far from constituting a “ public place virtual” – as the owner of

Is it a coincidence that the politician who best defines this era is Donald Trump?

***

Haidt is not discouraged, however. He propose thus a series of measures that he believes are likely to improve things. They include banning smartphones in schools, imposing a minimum age of 16 for creating social media accounts and, best of all, encouraging young people to (return to) playing with their peers, in the real world, without constant adult supervision.

With all due respect to the author, the simple political reality is that these Web giants have accumulated such economic and political power that any measure, however modest, will be vehemently contested. There are many, many money at stake. The way Meta reacted to Canadian and Australian laws proves it.

And there are also many, many of people — all generations combined — who are very dependent on their phones and the time spent on these social networks.

This week not only marks the release of the book The Anxious Generationbut also the 25e anniversary of that of the film The matrix. As pointed out by a recent essay in the Wall Street Journalthe film, which presented a dystopian future where human beings are slaves to machines, is even more relevant today than it was in March 1999.

Today, so much loneliness, anxiety and depression is the result of an addiction to a virtual universe limiting real relationships and stifling real life.

***

For both Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, the first step in resolving an addiction problem is to recognize its existence.

And what Jonathan Haidt presents is a hell of a problem. It is generational and collective. And, perhaps above all, heavy with implications for the most important democracy on the globe.

It remains to be seen whether, collectively, it will be recognized as such.